|

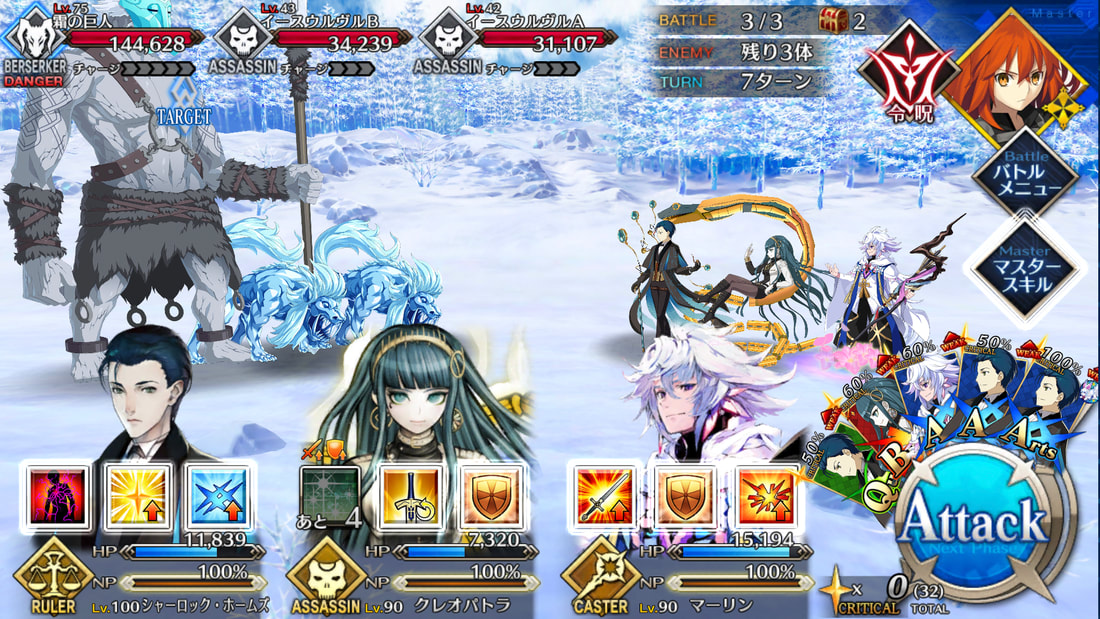

Free-to-play mobile games don't exactly have the best reputation. They are, generally speaking, timekillers, meant to draw players in with addictive gameplay mechanics and then entice players to spend money on individual purchases that can speed up play. There's nothing wrong with this model, of course, and games like that are great for when you have a few minutes to fill while waiting for something else, but generally speaking if you want a rewarding and high-value experience worth sinking hours and hours into, you probably want to look elsewhere. There is, however, a sub-genre of free-to-play mobile games that asks for a considerably larger time investment: gacha games. Gacha games, named after their trading-card-pack-esque monetization system, tend to be much more involved than something like, say, Candy Crush, usually centering on some sort of RPG-style battle system and asking players to build up strength over the course of many weeks and months in order to tackle the hardest content the games have to offer. These games have proliferated wildly over the past few years, and they have a (generally well-earned) stigma for being greedy time-sinks that can end up feeling more like work than play. These games usually feature characters from an existing franchise--Final Fantasy has at least three gacha games currently active, for example--and most gacha games rest heavily on that appeal. Passable RPG mechanics and strong licensing are often enough to maintain a profitable gacha game, which means many gachas don't have much of a reason to do anything particularly ambitious. They often become formulaic fairly quickly, Problematic as the style of game may be--and there's certainly a fair degree of controversy surrounding their gambling-esque purchasing systems--there is still room for the occasional gem. One such gem is Type-Moon and Delightworks's Fate/Grand Order, a rare example of a game that, rather than being weakened by its free-to-play mobile status, leverages the strengths of the platform in order to create a truly unique and exciting experience. I started playing Fate/Grand Order (hereafter FGO) in earnest while I was in Japan--one of my friend groups spent a lot of time playing it and talking about it, which got me more interested, although I'd had an account for a while before then--and about a year and a half later I still play actively. The game continues to grow and evolve in exciting ways, and I don't see myself dropping the game any time soon. A Rough Start As with most gacha games, FGO is based on an existing franchise--in this case, the works of the popular Japanese author Kinoko Nasu. Most of Nasu's works exist in the same general universe, with a few concepts and a very small group of characters who will occasionally pop up throughout his different books and games. His popularity in Japan coupled with his well-defined world made a Fate-themed gacha game a natural occurrence. The game features a wide range of characters from Nasu's works (as well as some original characters and some from works other authors have written in the same universe), and it takes the form of a series of visual-novel-style story chapters coupled with basic turn-based RPG mechanics. Given that the original Fate/Stay Night was itself a visual novel and that Nasu is a generally brilliant author, this all sounds like a really good idea. Unfortunately, early-game FGO was really bad. Although Nasu wrote the game's prologue, the first five main story chapters were written by other others, and the early ones especially clearly had little thought behind them. These chapters (which remain in the game, as the later game builds upon them), are largely nonsensical, consisting of bare-bones justifications for fighting various monsters-of-the-week. It's painful to read through and boring to play. Additionally, the game's battle system was not particularly well thought-out, and it was hugely unbalanced early on, with high-rarity characters in many cases being completely outclassed by lower-rarity competition, and with all kinds of inconveniences and annoyances built into the gameplay. To add insult to injury, the game's servers were highly unstable, often leaving the game down for days at a time, and new content additions were rare. By all rights, the game should have crashed and burned. That it survived this early time is a testament to how much people like Nasu's work. FGO may have been bad, but it was a game with Fate characters, and the premise of the game was interesting enough to make people stick with it. And even more than that, it was a massive financial success. When one of Fate/Stay Night's main antagonists--Gilgamesh, the Sumerian hero--was added to the game, FGO jumped to the top of Japan's top-grossing app charts, where it has lived for the past three years. Fortunately, this financial success gradually led Delightworks and Type-Moon to start taking FGO more seriously. The quality of the game's writing has been gradually improving over the game's lifetime, and now FGO rightfully touts its focus on storytelling as a key advantage FGO has over other gacha games. The quality of the game's art and animations has similarly improved, and the list of notable illustrators and voice actors working on the game has steadily grown. Delightworks has added to and improved FGO's slapdash battle system piece-by-piece, and while the game would likely be stronger if its base mechanics were more sensible, the gradual improvements and the newfound attention to balance have turned FGO into a surprisingly deep and enjoyable RPG. It's kind of amazing to see how far FGO has come in the past three years--it's gone from being a fairly blatant cash-grab to being a unique and high-quality experience that's brought together a wide range of artists to collaborate on a massive, ongoing work of art. It's really pretty exciting to follow. A Contemporary Serial Novel The basic premise of the first of FGO's story arcs is that the world has ended due to someone interfering in key moments in history. A small group of researchers operating out of an institution named Chaldea summons "heroic spirits"--great heroes of history, myth, and literature--and travels to those key historical moments to return events to their proper path. The second story arc, which started about a year ago, has a slightly more complex premise, but the structure is basically the same. Every few months, the game adds a new story chapter, in which the main characters visit another location and time period, meet another group of heroic spirits, and solve whatever problem is happening. It's mostly science-fiction, albeit with some fantasy elements depending on the story chapter. The early game, again, was less than compelling. The story chapters were short and forgettable, and the characters were uninteresting and flat. Potentially intriguing figures like Emperor Nero or William Shakespeare were reduced to single gimmicks and often only had a few lines, and there was little sense of danger or urgency. The third story chapter has some nice character moments with Asterios (the minotaur from Greek myth), and the fifth story chapter has a higher sense of stakes, but the sixth story chapter--Camelot--is where the game really began to pick up. Camelot is noticeably longer (and more difficult) than the earlier story chapters, and it is also much more narratively complex. Camelot's antagonists have identifiable rationales for their actions, instead of just being evil for the sake of being evil. Characters have meaningful interactions and rounded personalities, and the overarching plot starts to take more of a central role. The following chapter, Babylonia, continues this trend, and starting with Babylonia each of the game's chapters becomes comparable in length and quality to modest-length visual novels. FGO's second story arc has been yet higher in quality (and also very long), to the point where it is legitimately exciting when a new story chapter is released. FGO now has a rich cast of complex heroes and villains, each with their own values and motivations, and the newer story chapters explore interesting moral and ethical dilemmas. FGO has, in effect, become the digital equivalent of a serial novel, except you don't have to pay anything to read it if you don't want to. What started off as just a cool concept--traveling through time alongside famous historical figures--has become an exciting ongoing story. Even though the story components of the game are entirely free, I would credit it with most of FGO's ongoing financial success. Chilling with Oda Nobunaga Even without FGO's recent narrative strength and the popularity of Kinoko Nasu's works, though, part of FGO's success has to be accredited to the fact that it's just a really fun concept. The heroic spirits in FGO range from household names--Thomas Edison, Frankenstein's Monster, King Arthur--to the relatively obscure--Charles Babbage, the father of the computer; the 11th-century assassin Hassan-e Sabbah; Tomoe Gozen, the woman warrior from The Tale of the Heike--and seeing those figures interact makes FGO quite interesting. Each character addition involves a high level of detail, from visual art to battle animations to voice acting, and it's always exciting when the game adds someone new. These character interactions factor heavily into the main story chapters, but they also play a role in the more comedic event stories. These stories are separate from the main story chapter and place FGO's heroic spirits in unusual and often funny situations. The Summer 2017 event, for example, featured six teams of heroic spirits in a cross-country race meant as an homage to Steel Ball Run, the seventh part of the classic manga Jojo's Bizarre Adventure. Seeing characters as diverse as Sherlock Holmes's James Moriarty and the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Nitocris interacting in that sort of a setting is something you aren't going to see anywhere else, and that alone makes FGO appealing. This applies to the game's gameplay as well. FGO involves using teams of three heroic spirits, and while these teams are often selected for their gameplay usefulness, it's entirely possible to run teams of related or thematically-appropriate characters. It can also be fun to pair unrelated characters who wouldn't usually appear together in the same work--there's something inherently amusing about Sherlock Holmes, Cleopatra, and Merlin traveling through time together to save the world. Gacha games aren't for everyone. They require a commitment over a long period of time in order to fully enjoy, and this long timescale is often somewhat of a disadvantage. FGO turns the structure of gacha games from a financial necessity to an artistic strength, which is a large part of why it stands as arguably the best gacha game on the market. Most games are released as complete and self-contained works--as they should be--but there's something really exciting about following along with a project that's continually growing and evolving, constantly wondering what's over the next horizon. FGO is something that couldn't have existed ten years ago. The confluence of modern technology, mobile gaming trends, and Kinoko Nasu's writing produced this phenomenon by sheer coincidence, but it's been managed well and I continue to look forward to seeing what comes next.

As with any always-online game, FGO will eventually end, and its time-traveling serial-VN narrative will end with it. Until that time, though, I plan to continue exploring the past alongside the Chaldea Security Organization. It's one heck of a ride. I was recently talked into attempting a "level 1" playthrough of Kingdom Hearts II, which means playing the game on the highest of its four difficulties and equipping an ability that makes it so the playable characters do not get any stronger throughout the course of the game. In case it's not obvious, this is exceedingly difficult--and yet, those who have completed such a run often say it's one of the greatest gameplay experiences they've had. I'm not yet sold on it (and for those familiar with the game, I've just finished Timeless River), but it has got me thinking about the appeal of difficult games. Difficulty in games can be a positive or a negative depending on the player and the execution. Some people just aren't fond of challenging games, and that's why many games have optional difficulty levels--those who'd rather just enjoy the story can play on "normal" or "easy" or what-have-you. Catering to players who enjoy a challenge, though, is considerably more complex, as games have to strike a balance between being challenging enough to feel meaningful while also being reasonable enough to be cleared. To further complicate this, not all players who enjoy challenging games have the same level of skill, so a hurdle that seems reasonable to one person may be insurmountable to another--and a seemingly-impossible task quickly breeds frustration, which can lead players to drop a game midway and to think negatively of the game or developer in the future. With all that in mind, it seems kind of miraculous that there are games that are widely-regarded for being exceptionally difficult but also fair and fun. If you look at games with positive reputations for difficulty, though, they tend to employ one or more of a few common strategies, each of which either mitigates the frustration of the repeated failures endemic in high-difficulty content or provides ways for players to tailor the difficulty curve to their individual preferences and skill levels. Do Touch that Dial! One of the most creative solutions to this problem that I've seen comes from The World Ends With You (although similar mechanics appear in other games). TWEWY has four difficulty levels, which is not in itself particularly unusual. What makes TWEWY's difficulty system unique, though, is that players can change difficulty levels at any time, and--pivotally--players are actively rewarded for doing so. Each enemy has four different item drops--one for each difficulty level--and in order to collect all of them and 100%-clear the game, players must fight each enemy on each difficulty. Additionally, the player can adjust his or her level at any time while playing the game, and reducing your level increases the likelihood that items will drop. This flexibility is important, and it's something many games (and especially older ones) avoid. The value in forcing a player to select a difficulty level at the beginning of a game is that it locks the player into one difficulty level for the entirety of a run, meaning any outside observer would know that someone who clears a game on "hard" was playing on that difficulty for the entire length of the game. Allowing players to change difficulties would theoretically allow someone to play through a game on an easier difficulty and then later switch the difficulty up and falsely claim they played through the game on the higher difficulty. This concern is somewhat misguided, I think. If someone is so concerned about bragging rights that they are going to lie about the difficulty level on which they played a game, they're going to lie regardless of whether the game allows difficulty-switching, and the number of times I've seen someone try to back up a claim to completing a game on a high difficulty with an in-game screenshot is exactly zero. Inflexible difficulty levels have no real positive benefit, and they can lock a player into an unpleasantly low or high level of difficulty. This is especially problematic considering difficulty levels are inherently vague, and it's difficult to gauge the difference between "normal" and "hard" without being able to try both, which leads to most players just selecting the default option when playing a game (which is usually "normal"). Just offering the flexibility to change difficulty levels mid-run is not enough, though. Anecdotal evidence suggests players are more likely to drop a game entirely than to lower the difficulty when confronted with a frustratingly challenging obstacle. In order to break the stigma on reducing difficulty, a game needs to actively encourage that sort of switching. TWEWY handles this through its drop mechanics. Players are rewarded--and, at times, explicitly encouraged--for reducing the game's difficulty, which means pretty much every player is going to spend a good deal of time changing the difficulty levels. By incorporating flexible difficulty into another game mechanic, TWEWY eliminates the psychological barriers around adjusting the difficulty, which means players confronted with a frustrating fight are much more likely to reduce the difficulty temporarily and come back later when they're better equipped to deal with a challenge. TWEWY's various rereleases lose this somewhat, but the original game had a highly unique battle system that required players to be doing completely unrelated things with each hand. This was a lot of fun, but it had a pretty severe learning curve and made certain fights a lot harder than they might otherwise have been. TWEWY's fluid difficulty system encouraged players to take their time adjusting to the game's mechanics, eliminating a potential frustration with the game. It's pretty brilliant. Failure is Cheap Another significant component of difficulty in games is the cost of failure, measured primarily in terms of time. Games penalize failure in all sorts of different ways, but they almost always amount to the same general thing: some activity or portion of the game has to be re-completed. In the most traditional sense, this amounts to being returned to the last save point or to the beginning of the level and needing to repeat the cleared portion of the stage. Many classic platformers have a "lives" mechanic, which means the first few failures move you back to the last checkpoint (a relatively small failure cost of time), after which the next failure results in needing to redo the entire stage (a relatively large failure cost of time). More and more often, though, you see this failure cost being minimized. When a section of a game is very difficult, it can be fun to attempt it again and again, getting gradually better until you're finally able to clear it. What isn't fun is returning to that point of difficulty, especially when the lead-up to the challenging moment is not particularly hard or interesting. If, for example, a stage in a platformer contains a difficult element, such as a long series of jumps, near its end, and the player is required to replay the entire stage each time he dies to that element, the player ends up wasting a great deal of time replaying long stretches of the stage that he or she has already mastered. If, hypothetically, the stage takes approximately 5 minutes from the beginning until the difficult section, the section itself lasts 30 seconds, and it takes the player 20 attempts to clear, that means by the end the player has spent 10 minutes on the actual challenge and almost two hours on the drudgery that is returning to the point of difficulty. This becomes frustrating very quickly, and it severely tests a player's patience. Unless the lead-up to a challenging sequence in a game is explicitly part of the challenge, there is no disadvantage to minimizing the cost of failure. Frequent check-points and fast reloads can take the time required for repeated attempts of a difficult section of a game from minutes down to seconds, and the impact of this is twofold: not only does it minimize the player's frustration at the time required, but it also makes it easier for the player to see progress on the challenging sequence itself. It is much easier to learn to clear a difficult part of a game if the repeated trials are not interrupted by other irrelevant gameplay sequences. For extreme examples of games effectively minimizing the cost of failure, look to indie platformers like VVVVVV and Super Meat Boy. These games feature sequences of highly difficult platforming challenges, but checkpoints are so frequent that the cost of death is essentially zero. There is not even a loading screen breaking up the action--if you fail the platforming challenge, you simply reappear at the edge of the screen, ready to try again and again until you get it. This sort of forgiveness turns difficulty into something like a puzzle, encouraging players to experiment and find ways to eventually clear things. High costs of failure discourage experimentation, but with low time-costs of failure, a player can try something unusual fairly easily. If it works, great; if it doesn't, the player has only lost a few seconds of time. A platforming sequence can take twenty or thirty attempts and still only eat up ten minutes or so, minimizing the likelihood a player will get frustrated. This philosophy isn't necessarily limited to platformers, either. TWEWY, for example, allows players to immediately retry any fight after losing, eliminating the irritation of having to sit through pre-battle cutscenes again and again on repeated attempts--a common complaint especially in older RPGs. Similarly, Atlus's Catherine is a furiously difficult block puzzle game that manages to avoid being unnecessarily frustrating largely due to its generous check-point system. The Game's Cheating! Arguably the most important component of fun difficulty in a game is a sense of fairness. Even in very difficult games, the game's rules and expectations need to be clear and reasonable, and the game has to adhere to those expectations well. Nothing is quite so frustrating as a death in a difficult game that springs from a glitch rather than from player error. Nearly clearing a difficult fight only to get stuck in a wall or to fall through the floor is incredibly irritating and can easily drive a player away from a game. Bugs like that are fairly common, especially in larger games, and easier games have a bit more room for error in that regard, for two reasons that feed into each other. Easier games tend to require less exacting play, so while technical issues may be annoying they're much less likely to result in a player death than they would in a situation where a single hit can be fatal. Similarly, in easier games a single random death due to bad luck is much less frustrating than it would be in harder games, as those sorts of setbacks are rare and can be recovered from with relative ease. In a very difficult game, unfair deaths compound the frustration of the difficulty and may make it feel as if the game is unreasonable or impossible. Even beyond true glitches, though, difficult games need to be technically exacting in order to work well. A game that requires a high degree of player skill must in turn always respond the way the player expects. Inconsistencies or weak control schemes can leave a player feeling at the mercy of luck. An example of this would be camera control in the earlier Kingdom Hearts games. Although Kingdom Hearts II is significantly better than the original game in this regard, there have still been moments in my level 1 playthrough where the imprecise lock-on targeting mechanics have suddenly sent the camera in the wrong direction, leaving me open to attack from off-screen. Problems like that are forgivable in moderation, but they do add a level of frustration if they're a consistent issue. The Lethal Elevator Attendant There are, of course, some games that get away with just being completely unforgiving. You might call this the Atlus approach, due to the company's (now somewhat outdated) reputation for making infuriatingly hard games. Some games can have random deaths, heavy failure costs, and inflexible difficulties, and still do just fine. How do we account for those?

In a few cases, like Dark Souls or Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne, the punishing, old-school design philosophy is treated as part of the charm, and the types of players who gravitate towards those games take a sort of masochistic satisfaction in the frequent and costly deaths. These games by design do nothing to reach out to players who may have less of a tolerance for that sort of frustration--they embrace the frustration and revel in their difficulty. Even these games, though, have ways of reducing the challenge. Nocturne, in particular, offers enough customization that you can usually build a team to mitigate the randomness and challenge of most fights, and in Dark Souls certain playstyles make the game noticeably easier than others. Nocturne is specifically built around the trade-off between preparation and difficulty, while in Dark Souls this de-facto flexible challenge comes across as more unintentional, but regardless, the unforgiving facade is just that: a facade. For truly unforgiving-but-still-fun games, you have to look to more arcade-inspired works, like bullet hells and fighting games. The Touhou games are a great example of this. Touhou is considered a bullet hell--sort of like an evolution of the old arcade space shooters. Imagine Galaga, but everything moves twice as fast and there are way more objects on screen at any given time. These games are hard, and if you run out of lives you have to restart the entire game from the beginning. It sounds like a recipe for frustration, but it works very well, for one key reason: progress in the game is not winning, it's getting better. If you play a game like Touhou, your goal is probably not to beat the game. If you're really good at the game, you're probably aiming for a higher score than the last time you played, whereas if you're newer to the series, you probably just want to get a little better, survive a little longer, make it a little farther. It's less a series of tasks (as most games are) and more the developing of a skill, like learning to play a musical instrument. With each playthrough, and each loss, you feel like you've improved a little, and so failure itself becomes a form of success. The reward for playing is intrinsic rather than extrinsic, so the game doesn't need to help the player along. The same applies to fighting games, like Persona 4 Arena. Most fighting games live and die by their multiplayer and online modes, but often there will also be single player game modes that range from pretty easy (aimed at new players to help them learn the game) to stupidly, absurdly hard. The Persona 4 Arena games include a "score attack mode," which pits the player against a series of enemies with ridiculous advantages, to the point where the final enemy--a supernatural elevator attendant named Elizabeth--can heal herself to full at any time. Every time she does this, she taunts the player with a single cheeky line: "Do you have a problem?" While this is somewhat frustrating at first, eventually the absurdity of the challenge sinks in and it just becomes fun. Score Attack is not tied to any story mode and the rewards for clearing it are fairly minimal, so it can afford to be completely unfair and horribly unforgiving. When asked, "Do you have a problem?"--a problem with the completely imbalanced power of the enemy, a problem with the hours and hours of retries the fight likely requires--the answer, I find, is usually, "No, not at all." The cost of failure is low--you just retry the fight from the beginning--and the eventual satisfaction of victory is a huge rush. Score Attack doesn't even pretend to be fair, and in the original game there was no lower-difficulty option, so clearing it feels almost rebellious, like you're doing something that really shouldn't be possible. By intentionally embracing that attitude and philosophy, it circumvents the usual laws of frustration in difficulty. A few weeks ago, Rockstar released their much-anticipated game Red Dead Redemption 2. The game has, of course, generated a great deal of discussion, and while I have not played the game, I have noticed one particular discussion point emerging again and again: the game's borderline-obsessive focus on detail and realism. From accounts of examining in detail every object in a house, to needing to go through several intricate steps to completely load and fire a weapon, the game strives to emulate the real world as much as possible, and it leaves very little to the imagination. Whether this is a positive or a negative is somewhat open to interpretation--and the general response seems to be somewhat ambivalent--but it does, I think, point toward a trend in gaming away from asking players to suspend their disbelief. Suspension of disbelief is a concept most commonly associated with theatre (though it shows up in the context of other media as well). When watching a play or a musical, the audience is implicitly asked to temporarily accept that the people on stage are not actors, but rather that they are the people they are portraying. The audience may accept that a pantomimed prop exists, or that a character's soliloquy is actually an internal monologue none of the other people on stage can hear. This is such an integral component of theatre in general that we often don't even think about it until our instinctive suspension of disbelief is challenged (as in, for example, Tom Stoppard's deconstructive plays). Video games also used to rely heavily on this concept, and some, of course, still do. We accept that a character can take several arrows and sword slashes and come away fine just because he has a high health pool, or that you can traverse vast distances in a single screen transition. As technology has progressed over the past twenty years or so, a hallmark of major, big-budget titles has been the push to look and feel more and more realistic, using improved technological capabilities to do things like rendering progressively more real-looking character models and creating worlds that are entirely interconnected rather than divided into distinct chunks. It's super cool to see how games are changing and progressing in this regard, and realism absolutely has a place. That said, there comes a point where an intense focus on realism and detail start to compromise games in other ways. Just as a hyper-realistic set and over-the-top costumes are not necessary to produce a strong play, a game need not emulate reality in order to be effective. Suspension of disbelief is not a bad thing, and doing everything possible to ensure players never question a game's world can itself cause problems. Too Real; Not Real Enough One element of Red Dead Redemption 2's detail focus that has drawn some attention is its personal hygiene mechanics. The player has to ensure that the player character cleans his weapons and bathes periodically. This is, presumably, meant to add to the "realism" of the game--and it may work fine within the context of the overall experience--but I have to question the value of including such mechanics for the sake of nothing more than realism. Mundane tasks, like bathing or cleaning, occasionally pop up in games--and weapon maintenance/repair systems arguably fall under this umbrella--but usually do not benefit the player when performed and actively harm the player if ignored. This is the most "realistic" way of handling these systems, but it also tends to be the most annoying. Unless these mundane tasks directly impact the way the game is played in a meaningful way (like with weapon durability in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild), these requirements end up being something of a recurring, unproductive waste of time. A game as committed to detail as Red Dead Redemption 2 can maybe get away with this sort of thing due to its underlying philosophy of realism over traditional conceptions of what is fun in a game, but it can easily result in a reaction to the effect of, "I get the point, I'm a real person, why do I have to do this again and again?" Decisions that prioritize concept over player enjoyment need to be undertaken with caution, or else you're left with situations like Persona 3's battle system, which adheres strongly to the premise that you are the player character and can only issue general guidance to your allies, but which also generates a great deal of player frustration due to the frequent AI-related deaths. In most cases, this frustration results when a game's commitment to realism creates obstacles or annoyances for the player without also following through to situations in which it would benefit the player instead. To use the Persona 3 example again, not having control over party members would be far less bothersome if the party members made reasonable decisions, but the AI scripts for the allied characters result in them making choices no rational player would make--like trying to charm a charm-immune enemy instead of healing a near-dead ally--which not only frustrates the player but also breaks the illusion of the party members being intelligent, free-thinking individuals. In Red Dead Redemption 2, a similar issue seems to arise with the way the game defines realism. While there is a great deal of detail to the world, certain elements that are intended to feel realistic, like slowly examining each object piece-by-piece in the course of a search, may ring false. I read an insightful comment recently observing that a criminal looking for something in particular is unlikely to carefully pick up and turn over each object in a room--it would be far more believable to quickly tear the room apart until the desired object was found, even though such a search would not necessitate as much detail. Similar cracks in the game's realism appear in the limited options for character interaction, where most NPCs can be approached either by greeting them or shooting them, without much in-between and with little room for nuance. It's pretty much impossible to create a completely realistic experience in a game, with the possible exception of a tabletop RPG run by a highly experienced DM. Therein lies the problem with promoting realism over player enjoyment: it teaches players not to suspend disbelief, which then makes holes in the game considerably more jarring. Less-than Willing That mindset, though, is somewhat pervasive among the gaming community at the moment. I had a discussion with someone in the past week who criticized Persona 5 for an element of its narrative structure--it has a large number of scenes that can happen in any order (as determined by the player), and these scenes do not change to reflect which other scenes have been viewed, meaning some characters can appear to have significant character development only to return to disavowed behaviors shortly after. It's a fair criticism, but I think it also shows the insane level of detail we've come to expect from large games. While it would absolutely be more realistic for Persona 5's characters to behave slightly differently in each scene depending on which other scenes have already been viewed, this level of nuance would be a herculean task from a writing perspective--and Persona 5 already has a mammoth of a script as it is. The game asks for suspension of disbelief here, for us to accept that sudden realizations through the course of side-story character development will not be immediately reflected in the main plot, largely because it wouldn't be feasible for a company of Atlus's size to do the alternative.

Crucially, in this case, Persona 5 is not a game that rests heavily on realism. It is a stylized game that operates largely on the level of metaphor and symbolism. It does make a point of portraying mundane elements of daily life, but it always does so in bite-sized, aesthetically appealing chunks, not trying to reflect reality but rather using representations of the mundane in order to support its overarching message of the importance of taking action in order to right problems seen around you. To impose a desire for absolutely realistic and context-sensitive behavior on Persona 5 is to not meet the game on its own terms. Persona 5 is, of course, far from the only game to rely on the player to fill in inevitable gaps, but its massive size makes it a particularly good example of why expecting realism in all things is problematic. Games development, as with anything else, is resource-constrained. Devoting time, attention, and money to any one aspect of a game by definition means not dedicating those resources to something else. Red Dead Redemption 2 has the benefit of coming from a very large studio that has the resources to create a large game with painstaking levels of detail (although this may come at some degree of human cost, judging by reports of extreme levels of overtime at Rockstar), but small and mid-sized studios don't have that luxury. While development time could be spent on things like highly nuanced reactions to player choice and detailed representations of certain actions and behaviors, that isn't the best use of resources in every case. If this sort of detail would not fundamentally strengthen the game, the resources are likely best spent on more impactful aspects of the game. The expectation of absolute realism makes it harder as a player to accept these inevitable trade-offs and can lead to developers attempting to completely avoid those trade-offs, to the detriment of the overall experience. Ultimately, each game is different, and what works for one may not work for another. Intense realism has a place, but it is not the right approach for every game, and games should not all be judged on the basis of realism. Last week I wrote about the play Our Town, which is typically performed without a set. To criticize a production of Our Town for lacking elaborate set pieces would be to completely miss the point of the play. The same logic applies to criticizing games for lacking realism when realism is entirely unrelated to purpose of the game. Each game should be met on its own terms and judged on its own merits--there is not one set of criteria that fits every work. 2015 saw the release of a strange anime series called Death Parade, which is perhaps best known for its exceptionally catchy opening theme, "Flyers." The colorful, explosively energetic song was many viewers' (myself included) first encounter with the quirky Japanese band Bradio, and it gained a reputation for being among the most "misleading" anime opening themes in recent memory. Bradio describes their musical style as a hybrid of rock, funk, soul, and disco, and Death Parade's opening features the anime's characters dancing along with one of the band's most upbeat pieces, so the muted, semi-Absurdist show that follows the opening strikes many as discordant with the opening's tone. The positivity is, however, thematically in-keeping with Death Parade's message, and it serves as a reminder throughout the show that for all its dreariness Death Parade is not a fundamentally cynical show. Death Parade has a number of interwoven thematic ideas (any number of which could make for full posts), but the most interesting to me is the way it echoes Thornton Wilder's 1938 play Our Town--and particularly the play's third and final act. A central contention of Our Town is that most people do not fully appreciate their lives as they live them, a truth the play's central character does not realize until after her death. Not only does Death Parade echo this theme, but it also echoes Our Town's execution of this theme, right down to the structure of its climactic moment. Billiards in the Afterlife Death Parade's basic premise is fairly simple. It follows a man named Decim who runs a bar for the recently deceased. His job is to place people in psychologically trying situations in order to determine whether they are worthy of being reincarnated. The first several episodes are largely isolated in nature, showing individual examples of the judgment process and exploring the role of compassion in justice--one of the major themes I'm not planning to address directly today. As the show progresses, though, the focus shifts to the woman serving as Decim's assistant, who is revealed to be a recently deceased person herself. Decim was unable to judge her within the typical time frame for such decisions, so he temporarily employed her in order to monitor her over a longer period of time. Decim's role is comparable to the Stage Manager in Our Town's third act. He serves as a guide to the black-haired woman just as the Stage Manager serves as a guide to Our Town's Emily. While the premises are somewhat different--Our Town's afterlife focuses on moving on, while Death Parade's afterlife is centered on reincarnation--there are tonal similarities. Our Town is a fairly calm and slow-moving play, meant to replicate the pace of life in a small town, and despite Death Parade's higher stakes it tends to strike a similar tone. Death Parade's relatively colorless and minimalist setting--the majority of the show takes place within a single room--mirrors the way Our Town is usually performed, with no set or props. In both, the focus is entirely on the acting, on the people. There is drama, but little action. From Surrealism to Hyper-realism Our Town's three acts each focus on different moments in time, and the third and final act takes place shortly after the death of the character Emily. The act is set in the town's cemetery, and it features Emily talking with the town's other deceased, as well as with the Stage Manager. The scene is oddly surreal, especially following the relatively mundane portraits of daily life that are the former two acts. Towards the end of the act, Emily is given the opportunity to revisit a day in her life. She is warned against doing so, but she chooses to do it anyway. In David Cromer's 2008 off-Broadway interpretation of the play, this return to the past is accompanied by the sudden reveal of a hyper-realistic set depicting a period-appropriate home, complete with the smell of bacon cooking. This sudden sensory overload associated with being brought into something intensely real from the relative abstraction that is Our Town's depiction of the afterlife creates a strong emotional response in the audience, and it causes Emily's despair when she realizes how she and the people close to her squandered their time together to resonate quite strongly. Death Parade's climactic scene is almost identical. After spending a great deal of time talking with the black-haired woman in the stagnation of the bar, Decim allows her to return to her home--albeit in the present, after her death, rather than to a point at which she was alive. The effect is largely the same as Our Town's. In place of the unchanging, abstract scenery that is Decim's bar, the viewer is suddenly presented with a heavily detailed, highly realistic portrayal of a standard Japanese home. As she walks through the house, the black-haired woman sees flashbacks of her life with her parents, including--just like in Our Town--a family meal. She approaches her mother and tries to speak with her, but Decim informs the black-haired woman that she cannot actually interact with or change anything she sees. The realization of what she has lost, and how little she appreciated what she had, washes over the black-haired woman, and that emotional response is, somewhat paradoxically, what leads to her accepting her death. While the specific details are slightly different, these two climactic scenes mirror each other quite closely. Decim is the Stage Manager, and the black-haired woman is Emily. In both scenes, the mother character prepares a favorite food for the daughter--though in Death Parade's case, it's an offering to the deceased. Both Emily and the black-haired woman desperately plead for the attention of the living even after being told it is futile, and both characters ultimately conclude that they did not truly appreciate their lives when they were living. In both cases, the sudden shift of scenery strengthens the audience's response to the scene. Modernism and Noh There is, of course, no way of knowing whether this is meant to be a direct reference to Wilder's play--it may just be that Death Parade is influenced by modernist theatre more generally. Watching Death Parade feels in many ways more like watching a play than watching an anime, largely due, I think, to the central set piece. Decim's bar itself resembles a Noh stage in its structure, featuring a long hallway connected to a central area where most of the action happens. The hallway roughly matches the bridge on the side of a Noh stage--the bridge symbolizes the connection between the world of the living and the world of the dead, while the bar's hallway serves this function in a literal sense, as the elevator at the end of the hallway carries guests from the world of the living into the afterlife. There is, additionally, a balcony section in the bar where characters occasionally sit and watch the action taking place in the central "stage" area, mirroring the audience's placement around a Noh stage.

Our Town was itself partially inspired by Noh theatre, and Noh influences pop up in many Modernist plays. It may be that Death Parade echoes Our Town as a result of a shared Noh influence, but I think it's more likely that Death Parade's Noh influences are intended to relate to its more modern theatrical inspiration. Death Parade also exhibits shades of Theatre of the Absurd--particularly in context of its take on the concept of justice--in the way it highlights the breakdown of communication among people trapped in a meaningless world. Theatre of the Absurd also tends to draw from Noh (such as in the case of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot), which lends additional significance to Death Parade's interlinked Noh and modern theatrical parallels. Taken as a whole, Death Parade looks like an attempt to create a Modernist play within the context of an anime. From the similarities to Our Town to the Noh influences to the Absurdist ideas, it almost feels like it was written to be staged rather than animated. It even utilizes certain metatheatrical concepts, such as the occasional presence of an audience within the show or the recently deceased characters being mannequins acting like people rather than actually being the people themselves--indirectly drawing attention to the fact that Death Parade is a performance rather than a reality. In drawing on the likes of Wilder and Beckett, Death Parade strengthens its own arguments and grants itself a weight it might not otherwise have. If nothing else, it results in a type of story that's fairly unusual for an anime, which is thoroughly intriguing in and of itself. |

Isaiah Hastings

A Japanese Lit major and aspiring game designer with a passion for storytelling and music composition Archives

August 2019

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed